How kbmMW gets the best of both worlds — fast search AND fast iteration — by hiding a sorted linked list inside a balanced tree.

Contents

- 1 Why Should I Care?

- 2 The Big Idea (in Plain English)

- 3 What Is a Red-Black Tree, Anyway?

- 4 Addition #1: The Hidden Linked List

- 5 Addition #2: A Third Color for Duplicates

- 6 “Find Nearest” — The Killer Feature

- 7 The Sentinel Node Trick

- 8 A Real-World Example: The LRU Page Cache

- 9 Bonus: Cleaning Up Without Recursion

- 10 The Cost: What’s the Trade-Off?

- 11 Summary

Why Should I Care?

Imagine you’re building something that needs a sorted collection of items — maybe prices, timestamps, page numbers, or scores. You’ll need to do several things with it:

📋 Walk items in order

🔍 Find a specific item

⚡ Get the min or max

📐 Range queries

“Flush all cached pages from lowest to highest.”

“Is page #4721 in the cache?”

“What’s the oldest entry?” – instantly.

“Give me all orders between $50 and $200.”

Delphi gives you two built-in options, and neither is great at all of these:

| Operation | TList (sorted) | TDictionary | RB + Linked List |

|---|---|---|---|

| Find by key | O(log n) binary search | O(1) hash | O(log n) |

| Insert / Delete | O(n) — shifts elements | O(1) | O(log n) |

| Walk in sorted order | O(n) — natural | Not possible | O(n) — via linked list |

| Get min / max | O(1) | O(n) — must scan all | O(1) |

| “Find nearest to X” | O(log n) | Not possible | O(log n) |

The linked red-black tree in TkbmMWRBTree gets a green checkmark across the board. It’s the Swiss Army knife of sorted containers — and it does it by combining two classic data structures into one.

The Big Idea (in Plain English)

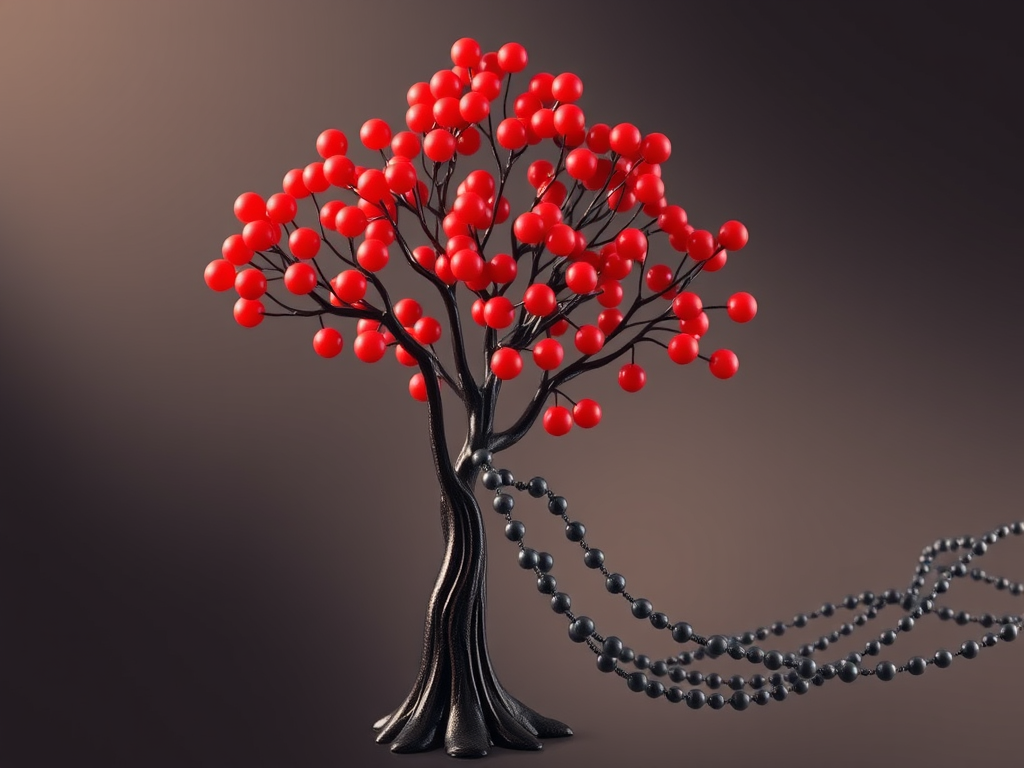

Picture a tree — like an org chart — where every item is stored in a node. The tree is arranged so smaller values go left, larger values go right. This gives you fast search: start at the top, go left or right at each step, and you’ll find your item in about log₂(n) steps. For a million items, that’s only ~20 steps.

Now picture a chain — a linked list — where all those same items are strung together in sorted order, like beads on a string. This gives you fast iteration: just follow the chain from one bead to the next.

The trick: every node lives in both structures simultaneously. Each node has tree pointers (left child, right child, parent) AND linked list pointers (previous, next). One set of nodes, two ways of navigating them.

The same 7 nodes exist in both views. The tree gives fast search. The linked list gives fast in-order walking. Dashed lines show they’re the same physical nodes.

What Is a Red-Black Tree, Anyway?

If you’re not familiar with red-black trees, here’s the 30-second version. A red-black tree is a binary search tree (smaller items go left, larger go right) with one extra rule: every node is colored either red or black, following rules that guarantee the tree never becomes badly lopsided.

The coloring rules ensure that the longest path from top to bottom is never more than twice the shortest. That means search, insert, and delete all take at most O(log n) steps — about 20 steps for a million items, 30 for a billion.

When you insert or delete, the colors might temporarily violate the rules. The tree fixes itself with rotations — small local rearrangements that restore balance. This is the standard textbook stuff, and kbmMW implements it faithfully.

The interesting part is what kbmMW adds on top of the standard algorithm.

Addition #1: The Hidden Linked List

In a standard red-black tree, each node has three pointers:

FLeft — my left child (smaller values)FRight — my right child (larger values)FParent — the node above mekbmMW’s TkbmMWCustomRBTreeNode adds two more:

FPrev — the previous node in sorted orderFNext — the next node in sorted orderThese two extra pointers form a doubly-linked list that threads through all the nodes in sorted order. The tree itself also keeps track of FFirst (the smallest element) and FLast (the largest element).

Think of it like a book with both a table of contents (the tree — lets you jump to any chapter quickly) and page numbers (the linked list — lets you flip from one page to the next).

Why not just walk the tree in order?

You can walk a tree in order — but it’s slow. Going from one node to the next in a standard tree requires climbing up to a parent and then descending back down. Each step costs up to O(log n) — and if you want to visit all n items, that totals O(n × log n).

With the linked list, going to the next item is one pointer hop. Visiting all n items costs exactly n steps. That’s a massive difference when you need to iterate frequently.

Tree traversal requires climbing up and back down. The linked list just follows one pointer.

Why doesn’t the linked list break when the tree rotates?

This is the key insight that makes the whole design work. When a red-black tree rebalances itself after an insert or delete, it performs rotations — small rearrangements that change parent-child relationships.

But here’s the thing: rotations never change the sorted order of the elements. They only change the shape of the tree, not which values come before or after which. The linked list represents the sorted order, so it doesn’t need to change when the tree rotates.

The tree looks different after a rotation, but the sorted order 30→40→50→60 hasn’t changed. The linked list is unaffected.

This means the rotation code doesn’t need to be modified at all. The linked list pointers (FPrev / FNext) are only updated during insert and delete — never during rebalancing. That keeps things simple and fast.

Addition #2: A Third Color for Duplicates

Standard red-black trees only allow unique keys. If you insert a second item with the same key, you either overwrite or reject it. But in many real-world scenarios, you need duplicates — multiple orders at the same price, multiple events at the same timestamp.

kbmMW solves this by introducing a third node color: mwrbtcDUP (purple in our diagrams). Here’s how it works:

When you insert a key that already exists, the new node is colored DUP and placed only in the linked list — right after the existing nodes with the same key. It’s never added to the tree. No tree pointers, no rotations, no rebalancing. Just a quick linked-list splice.

The DUP node (purple, starred) exists only in the linked list. The tree structure is untouched. Inserting a duplicate is just a linked list splice — O(1).

When you delete a tree node that has DUP nodes following it, the first DUP node gets promoted: it inherits the tree node’s position (left child, right child, parent, color) and graduates from a list-only node to a full tree citizen. The rest of the tree never knows the swap happened.

This is a clean design. No secondary lists, no wrapper objects, no extra indirection. DUP nodes use the exact same node class — they just don’t use their tree pointers.

“Find Nearest” — The Killer Feature

One of the most useful features is Find with the NearestLE (nearest less-than-or-equal) and NearestGE (nearest greater-than-or-equal) options. This answers questions like:

“I’m looking for key 45, but it doesn’t exist. What’s the closest key that does?”

The algorithm is simple. A normal tree search walks down from the root, going left or right at each node. If it reaches the bottom without finding an exact match, it knows the last node it visited. From there:

- NearestLE: follow the

FPrevpointer — one hop to the predecessor - NearestGE: follow the

FNextpointer — one hop to the successor

Search walks the tree, lands at node 40, misses. One pointer hop via the linked list gives us the nearest neighbor in either direction.

Without the linked list, finding the nearest neighbor after a miss would mean climbing back up the tree — multiple hops. With it, it’s a single pointer. This makes range queries wonderfully efficient: find the start of the range via tree search (O(log n)), then walk Next pointers to collect all items in the range (O(k) where k is the number of results).

The Sentinel Node Trick

One more implementation detail worth knowing: the tree doesn’t use nil for empty child pointers. Instead, there’s a single shared sentinel node called FNIL — a permanently black node with no key or data. Every leaf in the tree points to this sentinel instead of nil.

Why? It eliminates dozens of “if node = nil then…” checks throughout the code. Every child pointer always points to a valid object, so you can safely check its color or follow its pointers without crashing. It makes the rotation and rebalancing code significantly cleaner and slightly faster.

A Real-World Example: The LRU Page Cache

This isn’t just a theoretical exercise. Within the same kbmMW unit, the red-black tree is used to build a page cache for buffered file I/O — the kind of thing databases use internally.

The cache keeps recently-accessed pages (chunks of a file) in memory. When a page is requested, the system needs to:

- Check if the page is already cached — this is a tree search by page number. O(log n).

- If found, mark it as recently used — move it to the front of an LRU (Least Recently Used) history list.

- If not found and cache is full, evict the oldest page — grab the last item from the LRU list, flush its dirty data to disk, remove it from the tree, and reuse the slot.

- Walk all pages to flush — when shutting down, iterate through every cached page and write dirty ones to disk. The linked list makes this a simple loop from

FirsttoLastwith no recursion.

On Windows, the page buffers are allocated with VirtualAlloc and pinned in physical memory with VirtualLock — giving direct, page-fault-free access to the cached data. The red-black tree is the index that makes it all possible.

Bonus: Cleaning Up Without Recursion

Here’s a small but delightful payoff. When you need to destroy a tree and free all its nodes, the standard approach is a recursive traversal — visit every node and free it. But recursion can overflow the stack for very large trees.

With the embedded linked list, cleanup is trivially simple. Start at First, follow Next pointers, free each node. A flat while loop. No recursion, no auxiliary stack, no stack overflow risk:

n := FFirst;while n <> nil dobegin next := n.Next; n.Free; n := next;end;That’s it. O(n) time, O(1) extra memory.

The Cost: What’s the Trade-Off?

Every node carries two extra pointers (FPrev and FNext). On a 64-bit system, that’s 16 extra bytes per node. For most applications, that’s negligible. For a million-node tree, it’s about 15 MB of extra memory — a small price for O(1) iteration, O(1) min/max, and instant nearest-neighbor lookup.

There’s no runtime penalty during rotations (the linked list is untouched) and the linked list maintenance during insert and delete is O(1) — it’s just pointer shuffling at the insertion point, which the tree search already found for free.

Summary

TkbmMWRBTree takes a well-known data structure and makes it practical for real-world use by adding two things:

| Augmentation | What it gives you | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Embedded doubly-linked list | O(1) next/prev, O(1) min/max, O(n) full iteration, no-recursion cleanup, fast nearest-neighbor | 2 extra pointers per node |

| DUP color for duplicates | Multiple items per key, O(1) duplicate insert, no secondary data structures | One extra enum value |

The key insight that holds everything together: tree rotations don’t change sorted order, so the linked list never needs to be updated during rebalancing. The two structures coexist without interfering with each other.

If you ever find yourself needing both fast search and fast sorted iteration in Delphi — a sorted price book, a time-series index, a cache with eviction — this is the kind of structure that’s worth reaching for.

The kbmMW framework is developed by Kim Bo Madsen at Components4Developers.

![]()

Thank you it was very interesting read.

There is however another hidden cost, linked list and pointers in general are not cache friendly like other data structures. meaning that while some operations may have the same time complexity they will perform in order of magnitude slower than on contiguous data structures.

Hi,

Any algorithm should be selected for the purpose its about to be used for.

If it can be done using fixed arrays, then you will be able to benefit much more from the various caching mechanisms in CPUs, but you will often either have to spread the data over a large array, wasting storage, or you will have to brute force find stuff, specially in indexing/seaching like scenarios (find those with a value greater than x etc.)

In such search scenarios, more dynamic methods can be a better choise despite the penalty occuring by the less intensive use of the CPU cache.

Some algorithms combine the two approaches, by having linear searchable arrays indexed by some dynamic datastructure. They kind of takes the best of two worlds, but again, not always useful for all scenarios.

(Kim

This is really neat! It must add some extra book-keeping but I can see the clear benefits especially re ordered iteration. Very nice.

Do you have any measurements re the impact of 16 bytes extra on cache locality / performance? Or benchmarks on iteration in general? I’d love to see the impact in graphic form (I agree, I would fully expect this to be really useful.)

Hi,

I have not done specific comparative performance tests with and without the extra doubly linked list.

I am using it in a number of scenarios, like the caching mechanism, and for handling file based prioritized message queues.

Futher I have projects with specialized message queues (descending from the ones in kbmMW) adding searchable metadata (media stuff) that also benefits from them.

/Kim

(By the way, I’ve been reading your past couple of blogs on tech topics like this too, really enjoying the series.)

I’m happy you like it!

I will post some more when I get around to it.

/Kim